Image created by a botnet of 420,000 devices – watch 24 hours of global Internet activity in 8 seconds,

with the higher activity in reds and yellows, and the wave shape showing where it’s day and night.

The global digital language divide ÷

Try to visualise the Internet. For many, it is something hazy, suspended somewhere above our heads as we gaze at our screens. It’s composed of tiny, moving fragments of information and simultaneous conversations, and it has no defined edges: it is limitless.

This vision of the Internet as something infinite, open to be freely explored, is perhaps both naive and arrogant but, as an English speaker, it is not a sense of entitlement that is completely without reason. The first language used on the Internet was almost certainly English. By the mid 1990s it was estimated that English made up 80% of the content.

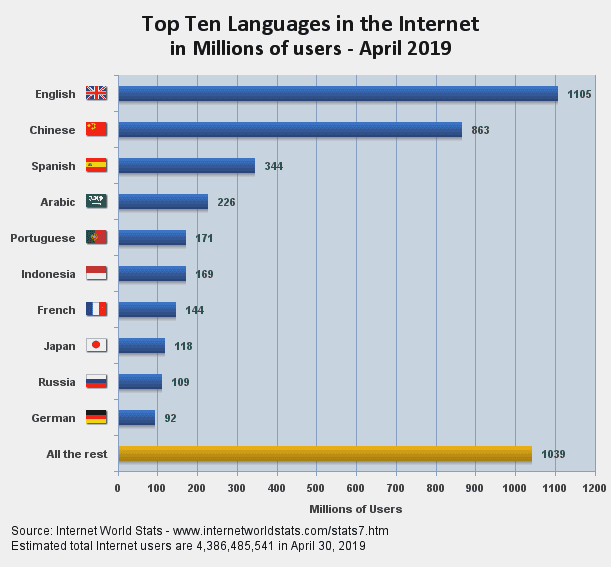

However, from once dominating the web, English now represents just one language in an online linguistic elite. English’s relative share of cyberspace has shrunk to around 30%, while French, German, Spanish and Chinese have all pushed into the top 10 languages online. Some of these have ballooned at great speed: Chinese, for example, grew by 1,277.4% between 2000 and 2010. Out of roughly 7,000 languages in use today, this top 10 make up 82% of the total Internet content.

Does the language you speak online matter? The unprecedented ability to communicate and access information are all promises woven into the big sell of the Internet connection. But how different is your experience if your mother tongue, for example, is Zulu rather than English?

The relationship between language and the Internet is a growing area of policy interest and academic study. The story emerging is one where language profoundly affects your experience of the Internet. It guides who you speak to on social media and often how you behave in these communities. It determines how much – if any – information you can access on Wikipedia. Google searching “restaurants” in a certain language may bring you back 10 times the results of doing so in another. And if your language is endangered, it is possible it will never have a life online. Far from infinite, the Internet, it seems, is only as big as your language.

Language and communities

“The Web does not just connect machines, it connects people,” said Tim Berners-Lee.

Language is just as important to building human connections online as it is offline: it forms the basis of how users identify with each other, the lines on which exclusion and inclusion are often drawn, and the boundaries within which communities grow around common interests.

A study of the most-edited topics in different Wikipedia language editions shows striking differences in what causes controversy in different online language communities. In English “George W.Bush”, “circumcision” and “global warming” made the top 10. In Hungarian, “gypsy crime” was among the topmost controversial issues, in French “UFOs” and “Jehovah’s Witnesses”, while in Czech “telepathy” caused disputes.

On Twitter, although English is the most common language, an estimated 49% of tweets are in other languages, with Japanese, Spanish, Portuguese and Indonesian users the most active. Analysis of user behaviour shows Twitter users tend to confine their follows, tweets and retweets to those that speak the same language so, while theoretically it’s a platform for global conversations, in reality these interactions are fragmented and often limited by language.

Twitter users in different languages are also likely to express different behaviours. Some languages by their very structure mean that you interact with the platform differently. For example, you can say more in the 140 character limit in Chinese than you can in English. Research has shown that Koreans tend to use Twitter to reply to each other, while German speakers share more URLs and hashtags, and if you are tweeting in Indonesian you retweet roughly five times more than in Japanese. Researchers concluded that different language groups use Twitter for different reasons: some primarily for conversation and others for sharing information.

Research in the Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology analysed bilinguals using Facebook in English and the Chinese equivalent, Renren, in Mandarin. It revealed that the same individuals behave in distinct ways on these different platforms. Users on Facebook displayed more individualistic tendencies while on Renren users more frequently shared posts that benefited the wider group.

Inequality of information

“The famous engine [Google] that recognises 30 European languages recognises only one African language and no indigenous American or Pacific languages.”

This is Daniel Prado, researcher on linguistic diversity, commenting on the issue of equality and languages online in 2012. While Google states one of its key goals is to expand the number of languages you can use on its search engine, there are inevitably huge challenges around inclusivity, particularly when many smaller languages remain only in oral form or without a standardised orthography. Nevertheless, out of an estimated 7,000 in use today, it is still the case that you can only Google search in just over 130 different languages.

Even for languages that are recognised not all have the same traction. This is vividly illustrated by research from academics Mark Graham and Matthew Zook, who compared the Google searches made in the West Bank in Hebrew, Arabic and English. They revealed a striking imbalance between linguistic groups; searches in Arabic in areas under Palestinian control usually result in only 5% to 15% of the number of results that the same search term brings in Hebrew. English searches also bring back between four and five times more results than in Arabic.

On Wikipedia there are huge asymmetries in the volume of online content in different language editions. Out of the 288 official language editions, English is by some distance the largest edition in terms of users, followed by German and then French. On the other side of the spectrum, there is a near absence of any content in many African and Asian languages.

And even if you speak a dominant language, you still get a limited view of the information available. You might assume that there would be many universal themes or popular historical events in common across different language editions. There is however less common content across language editions than you might expect: 74% of concepts have articles in only one language and 95% of concepts are in fewer than six languages on Wikipedia. Even English – the largest and potentially most diverse edition – contains only 51% of the articles in the second-largest edition, German.

Wikipedia is just one site, but even this small pool suggests the universe of information on the Internet looks very different from one language to the next. Perhaps philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous quote needs a one-word caveat to make it fully relevant for today: “The limits of my language online mean the limits of my world.”

Who and what gets represented online?

Inequalities in the information available for different languages online has implications for who and what gets represented – and by whom.

Research by Mark Graham and Matthew Zook shows the inequality of representation that emerges when you map which languages describe different geographies. Their visualisation illustrates which articles relate to different places in separate language editions on Wikipedia. The dominant language – English – has the densest information and greatest geographical spread. However, if you explore what the world looks like if you speak Hebrew or Arabic, a very different picture is painted. There are huge information vacuums in non-dominant languages, where people, places and cultures are swallowed into the dark. And when you look at places described by smaller languages on Wikipedia, it is notably the global south that disappears.

This information inequality, Graham argues, has the potential to reinforce colonial-era patterns of information production and representation. Another map, highlighting which language dominates the descriptions of different countries, shows that English, followed up by French, overwhelmingly dominates most of Africa, Asia and parts of eastern Europe. In short, it appears on Wikipedia at least, dominant languages (mostly from the western world) are amplified and end up largely speaking for those with less powerful voices.

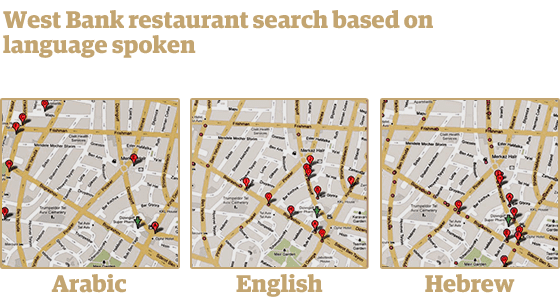

Inequality in information and representation in different languages online can also affect how we understand places and even how we act in them. In a case study of the West Bank, searching for “restaurant” locally in Hebrew, Arabic and English brought back different results for each language.

“Rich countries largely get to define themselves, and poor countries largely get defined by others.” –Mark Graham, Oxford Internet Institute

That Google can send Arabic speakers to one part of the city and Hebrew speakers to another when they are searching for the same thing could risk reinforcing social segregation in the city. This case study, Graham argues, should invite questions around the important economic, social and political responsibility of the company: “It isn’t good enough for Google to throw their hands in the air and point to their algorithms when asked why data are mediated and presented in certain ways. Whether they like it or not, they shape how millions of people interact with their cities.”

Bridging the divide

Translation technologies offer one solution to bridging online language divides, while also opening up new markets for businesses. Although currently only available in a few languages, last year Microsoft launched the Skype translator, and both Facebook and Twitter have also paired up with Bing to offer users translation services.

Scott Hale, data scientist at the Oxford Internet Institute, argues that more could also be done to unlock the power of multilinguals online. Internet platforms he believes could be modified to make it easier for multilingual users to find content in other languages, as well as encourage them to contribute in more than one language. “Many review sites, such as TripAdvisor and Google Play, prioritise reviews in a person’s selected user-interface language or even completely hide reviews not in the user-interface language,” says Hale. Platforms like Wikipedia, he says, could allow you to search a topic in multiple language editions at the same time.

Hale also found that although only 11% of people are multilingual on Twitter, and 15% on Wikipedia, these multilingual individuals are more active, writing more tweets and creating and editing more Wikipedia content. These people, he believes, could potentially challenge the Balkanisation of information and discussion online. Whether it is translating and bringing foreign concepts into different language editions on Wikipedia, or moving breaking local news stories to new language communities and different geographies, they have the power to be influential.

An interactive by the Global Language Network at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) illustrates the patterns and behaviours of these multilingual users. It shows which languages they are moving between on platforms, highlighting where there are strong links of information exchange and which languages are more isolated. Twitter, it reveals, has a particularly high number of Malay, Portuguese and Spanish users also tweeting in English, while on Wikipedia there is an even wider spectrum of foreign language users moving into English to edit pages.

Which languages will survive online?

In the paper ‘Digital Language Death’ researcher András Kornai predicts that 95% of all languages in use today will never gain traction online.

The paper claims to “present evidence of a massive die-off caused by the digital divide”. Will the Internet act as a catalyst for the extinction of many of the world’s languages? The issue of linguistic representation online is still a problem only for those who are able to access the Internet, with billions remaining digitally disenfranchised. However, as Internet access continues to extend to geographies and communities previously disconnected, and more users come online from the developing world, it seems sensible to assume that the linguistic elite will be challenged.

Access to the Internet also offers the opportunity for linguistic empowerment: to document and preserve languages, to share teaching material to encourage new speakers, to translate important information for marginalised groups, and even to create virtual communities of speakers where they may struggle to exist offline. The Endangered Languages project is one example of using online platforms to this end. The Internet can also be a place not only for languages to evolve, but to be invented or to find a second life. The project Muysccubun for example has been working to document and share the extinct Muisca language, historically spoken in central Colombia, by creating online dictionaries and building a community around their Facebook page.

Is there a danger however that instead new users, influenced by the volume of content in more dominant languages, will abandon their mother tongues online? Research has suggested that speakers of smaller languages online will often opt to use the Internet in a larger language, even if they don’t speak it well. This makes sense: if you are a bilingual speaker of English and Zulu for example, there are clear advantages to using the English edition of Wikipedia with close to 5 million articles, over the Zulu edition with only 685.

Inee Slaughter, executive director of the Indigenous Language Institute, points out the fact many indigenous languages only exist in oral form creates an additional barrier: “If the digital media is heavily literacy-based, the digital world is not friendly for indigenous language users.” It is possible that as the digital divide closes, instead of encouraging greater linguistic diversity, there will be a negative feedback loop where dominant languages are made even more prevalent.

What next?

In 2011 the UN declared access to the Internet as a basic human right. It is clear however that access alone is not enough to put everyone on an equal digital footing. As the Internet and social media become increasingly embedded in how we connect with and understand the world around us, so too does the language we use to access that experience. Today Unesco argues that speakers of non-dominant languages need to be able to express themselves online in culturally meaningful ways, and urges governments to develop comprehensive language-related policies that support and facilitate online linguistic diversity and multilingualism.

“The Internet is becoming the town square for the global village of tomorrow,” said Bill Gates. But if the vast majority of the world’s languages don’t have a digital future, what will speakers have to sacrifice to be heard in the “digital town square”? Closing the digital divide clearly has huge potential to empower individuals around the world. However, as it stands at the moment, looking through the lens of language leaves claims the Internet is an inclusive, egalitarian public space sounding more and more hollow.

Author of this article is Holly Young, journalist at The Guardian,

published on www.theguardian.com

![]()

sponsored by